The Mills of Juniper Green, continued...

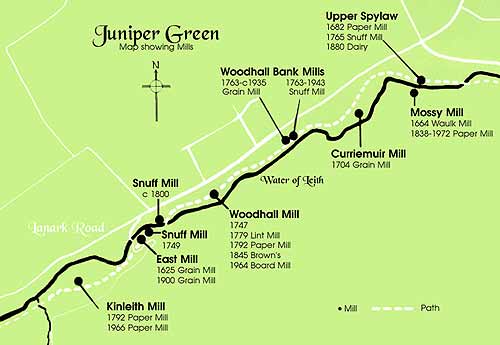

Along the Juniper Green stretch of the Water of Leith there was a concentration of watermills: seven in Juniper Green proper, and at least ten in which Juniper folk would have worked.

Map of the mills on the Juniper Green stretch of the Water of Leith. Adapted, with permission, by Rab and Della Purves, from John Tweedie's book entitled A Water of Leith Walk

Compensation reservoirs in the hills

One problem for the millers was the inconsistency of the water flow - in summer the river might dwindle to a trickle, in winter it might flood, as the hapless Reverend Spark of Currie found out to his cost when he was swept away by the disastrous floodwaters of 1739. The problem of an inconstant flow was exacerbated when in 1843 springs on the north slopes of the Pentlands were tapped to provide a pure supply for the population of Edinburgh for drinking and washing. So, compensation reservoirs were built at Harperrig, Threipmuir and Harlaw and these were regulated by a committee of mill owners and tenants.

Weirs, sluices and lades

An essential means of controlling the flow was by a system of weirs, sluices and lades.

Above the weirs (or damheads) were deep pools out of which the water flowed into lades (or millraces), narrow channels to increase the force of the flow.

You can still see impressive weirs above Kinleith Mill and Mossy Mill though the water in the lade at Kinleith drifts sluggishly in 2007.

The millers controlled the flow of water in the lades by wooden sluice gates.

Most of these have long since rotted away, but some of the sluice timbers survive at the head of the Kinleith lade and the remnants of a complex structure of brick and metal can be seen at Woodhall Board Mill.

Because of the dense concentration of mills on the Juniper Green stretch of the river, there was often more than one mill per lade and so it was vital that the millers got on well with one another. For, if one miller opened the sluice gate for his mill to operate, then the other mills on the same lade had to work as well or they would flood. The alternative was to have a relief sluice which acted as a bypass for the water. Traces of these can be seen at East Bank Snuff Mill and at Watt's Snuff Mill.

Waterwheels

There are three types of waterwheel: the undershot, the breast and the overshot. In the first, and simplest, type, the paddles of the wheel are turned anti-clockwise by the water flowing below. Most of the wheels in the Juniper Green mills were of this type which requires only a short lade.

The breast-wheel is turned by water falling over the side of a pit on to buckets below the axle. You can still see the wheel pit of East Mill Grain Mill through the brambles and nettles at the side of the Walkway.

The overshot wheel was a lot more efficient than the undershot wheel, but it needed a big head of water falling from above on to the buckets and driving the wheel clockwise. Some of the wheels on the Bavelaw Burn in Balerno were of this type.

Mills could be used for manufacturing a variety of products, and could convert from one use to another fairly readily. If the bottom dropped out of the market for a certain product, such as snuff. Then, the machinery could gear up for another product, like paper. The mills in Juniper Green were employed in grinding grain and snuff, making paper, and washing and waulking cloth.

Here are some details of the mills on our stretch of the river though none remain in 2007.

Kinleith Mill

Kinleith Mill started life as a waulk mill in the early 17th century but switched to papermaking in 1792. Kinleith is strictly in Currie, but many Juniper folk worked there. It expanded very rapidly with a huge output of top quality paper for books, for which there was an insatiable market in Edinburgh, the capital of the Enlightenment as well as Scotland's centre of finance, learning and the law. It made the owners, the Bruce family, rich enough to build a posh mansion for themselves at Glenburn in the hills above Currie. The manager and some of the workers lived in Blinkbonny. Kinleith had its own railway siding, an enormous chimney known as Willie's Lum, and rows of windows lighting the "salle" in which women piece workers stood at long tables in thick felt aprons inspecting the paper for flaws, flicking rapidly through the sheets, scrunching up the imperfect ones and stacking the flawless sheets in reams ready for cutting by the guillotine man. It was acknowledged that women were better at the finishing work than men because they could chat and work efficiently at the same time, thus making endurable what was otherwise a repetitive boring job. They did begin to flag, however, if they were assigned a place near the south-facing windows through which in summer the sun shone pitilessly. Kinleith went on making paper until it closed in 1966 and the workers received their redundancy notices.

However, Kinleith's name lives on in the big papermaking concern at Tokorua in New Zealand's North Island started by Sir David Henry who had worked his way up from office boy in the mill in Currie. Incidentally, one meaning of the word "Tokorua" is "to be thievish of small things" such as, perhaps, the name of a Currie paper mill.

The East Mills

Downstream of Kinleith and Mutter's Bridge are the East Mills. Their weir is upstream of the bridge under which the lade flows through its own culvert.

The grain mill there was built in 1625 and did not close until 1900. Using the same lade was the first snuff mill on the river, built in 1749, and specialising in the manufacture of cinnamon snuff.

On the other side of the river from the snuff mill is East Bank Mill, a barley mill built around 1800. It did not last long, possibly because the two mills on the opposite bank had first go at the water at that point. Or possibly the abolition of the slave trade two hundred years ago had something to do with its demise. Until abolition, barley from the mills had been trundled along the Lanark Road all the way to Glasgow from where it was shipped across the Atlantic to feed the slaves on the sugar and tobacco plantations. Then, back along the Lang Whang came the same carts laden in turn with West Indian rum and sugar for the Edinburgh markets, as well as tobacco for the snuff mills of Juniper Green.

The Woodhall Mills

Woodhall Board Mill was the next one downstream.

Apparently, Woodhall Board Mill, like Kinleith, converted to papermaking in 1792. Obviously, 1792 was a good year for the paper industry. It had a very elaborate sluice system, some of which can still be seen in 2007. It later switched to making cardboard packaging, especially for the whisky industry, which kept it going until 1984. Work was hard, noisy and dangerous. Lads often lost fingers in the machinery or burnt the skin on their hands from friction, and many workers went deaf from the incessant noise. However, there was fun too, though it is doubtful whether those who were about to be married appreciated being stripped naked and covered in dye just before their big day!

There were two other mills at Woodhall and these shared the same lade. One was Wright's Grain Mill which produced yet more barley; the other was Watt's Snuff Mill.

© Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

Watt's Snuff Mill

The latter kept going until 1940 and it was said that Bonnie Prince Charlie once declared that Watt's snuff was the best he'd ever sniffed. If this is so, Watt must have exported it to the various resorts in Europe between which the dissolute wannabe was drunkenly and aimlessly drifting for Watt didn't start up his mill until 1763, well after the Young Pretender had gone into disappointed exile. It seems more likely that John Watt and his son Robert were astute businessmen, old and young pretenders of a different sort, implying a By Royal Appointment credit for their product.

Curriemuirend Mill

Just upstream of the city bypass was Curriemuirend Mill, better known among today's Juniper residents as Inglis' Grain Mill. It was first mentioned, by the name of Denham's Mill, in 1704.

Under the ownership of the Inglis family, its products included oats for porridge and for feeding the racehorses at Newmarket. Unhappily, but aptly, this illustrates Dr Johnson's infamous definition of "oats" as a "a grain which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland supports the people"!

Replica waterwheel and ornamental pond at the flats at the site of Inglis Grain Mill in 2007

Operations stopped in 2001 and it is now in 2007 a modern housing development; the only references to the past are its name - Woodhall Mill - and a flimsy replica wheel beside an ornamental millpond.

But, upstream of the new flats, you can still see dippers bobbing on the stones of its once-purposeful weir.

Mossy Mill

Beyond the bypass, on the south bank, is Mossy Mill, named after its original owners, the Mosey brothers. It began in 1664 as a waulk mill, but later converted to papermaking.

The weir for Mossy Mill is impressive and the lade is unusual in going off from it at right angles.

On the bank above is the house once occupied by the manager and on the other side of the river is a tunnel leading to a bridge through and over which the mill workers trudged to work. Modern flats now occupy the mill site.

Upper Spylaw Mill

Like Mossy Mill, Upper Spylaw Mill, is really in Colinton, but Juniper folk would have worked in both. It dates from the 17th century and made paper before converting to snuff-milling.

The snuff miller, William Reid, was the arch-rival of the wealthy and successful James Gillespie who worked the nearby snuff-mill at Spylaw. Luckily, the daggers-drawn rivals did not share the same mill-lade. Under the pretext of investigating rumours of smuggling going on at Upper Spylaw, Gillespie's cronies, disguised as excise men, conducted a series of raids on Reid's mill, a case of industrial espionage, for they were really spying on Reid's new milling machinery. The tales of smuggling were, however, not without foundation, for a cache of brandy and a ton of tea were subsequently found at Upper Spylaw in an upstairs room accessible by an outside stair. The mind boggles at the thought of trying to find a hiding place for a whole ton of tea!

Juniper Green: in the right place at the right time

With such skulduggery going on next door, it is evident that Juni Green was not always a quiet, leafy, douce dormitory for the city of Edinburgh. Once it was a village, bigger than either Colinton or Currie, with its own reason for living, industry fuelled by the needs of the nearby city. And that industry owed its existence to the fast-flowing waters of a narrow, steep river, which in turn owed its existence ultimately to the effects of glaciation on the land. The river was formed thousands of years ago, but Juniper Green was lucky enough to find itself in the right place at the right time.

Bibliography

Balfour, Rev Lewis: "Parish of Colinton": New Statistical Account of Scotland: Vol 1 Edinburghshire: William Blackwood and Sons: Edinburgh: 1845

Cant, Malcolm: Villages of Edinburgh: Vol 2: John Donald: Edinburgh: 1987

Coghill, Hamish: Discovering the Water of Leith: John Donald: Edinburgh: 1988

Gauldie, Enid: The Scottish Country Miller 1700-1900: John Donald Publishers Ltd: Edinburgh: 1981

Jamieson, Stanley (ed): The Water of Leith: Water of Leith Project Group: Edinburgh: 1984

McCleery, Alistair, David Finkelstein & Sarah Bromage (eds): Papermaking on the Water of Leith: John Donald in association with SAPPHIRE: Edinburgh: 2006

Priestley, Graham: The Water Mills of the Water of Leith: Water of Leith Conservation Trust: Edinburgh: 2001

Thomson, A.G.: The Paper Industry in Scotland: Scottish Academic Press: Edinburgh: 1974

Tweedie, John: A Water of Leith Walk: Juniper Green Village Association: Edinburgh: 1974